Update 7 January 2022: Sincere apologies to all readers for my original failure to provide the crucial Willard & Bell (2021) reference with its link https://museum.bc.ca/brain/report-on-small-to-medium-non-profit-museums-governance/, now also in References Cited below.

Like everyone else in the third decade of the 21st century world, museum workers have been challenged for the past 2 years by the outcomes of 4 waves of pandemic.

The National Arts and Culture Impact Survey on COVID-19 for the Canadian sector’s “service organizations” & individuals was released in January 2021 (Borodenko 2021). Notably, for my purpose here, the sample was composed mainly from performing arts organisations including artists groups, theatre, music, & others (Borodenko 2021: 27, 28). Your blogger’s caution is that, of the 1,273 survey responses, only 7% receive heritage-related funding. The largest proportion of the sample (27-29%) obtains arts funding & most reported no funding (Borodenko 2021: 29, 30).

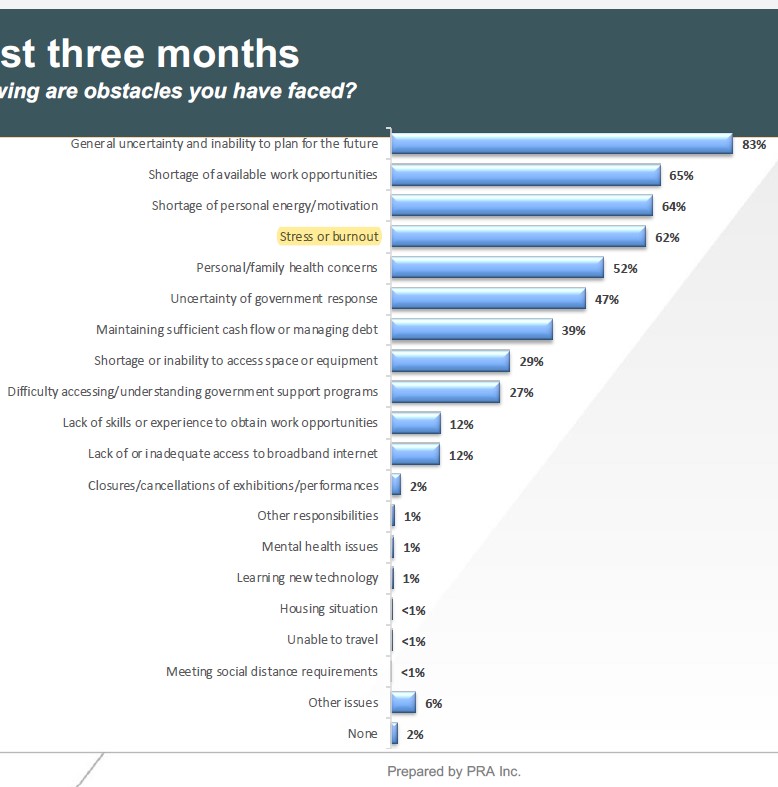

Nevertheless, in relation to several of this blog’s recent posts on “burnout” in the museum industry, a key finding of the above Survey is that the rate of respondents reporting very high or high levels of stress has exploded from 25% Pre-COVID to 79% at the end of November 2020 (Borodenko 2021: 23). From its Ontario Individuals report,

Almost all individuals say they have faced at least some barriers over the past three months, with the most common being general uncertainty and inability to plan for the future [that one intuits is a rather high stressor]. Respondents also commonly mentioned impacts on their emotional wellbeing, such as shortage of personal energy/motivation and stress or burnout . . . (p. 7) [emphasis added].

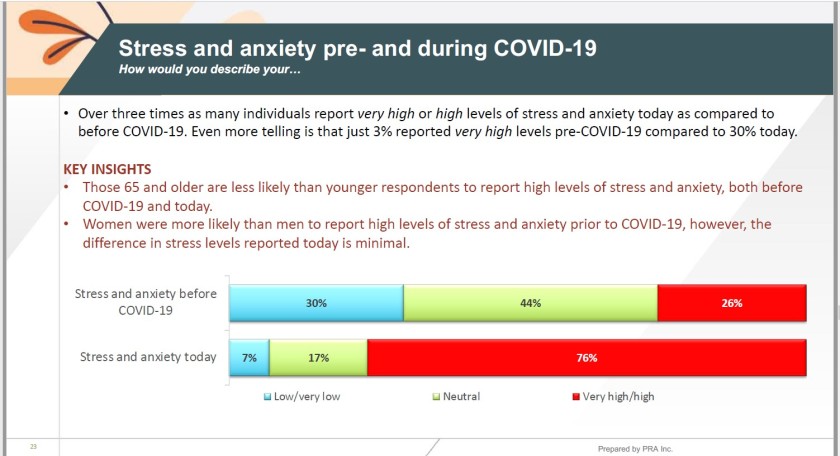

One part of this arts survey Key Findings includes: “4) Very high stress and anxiety levels suggest that the impact of the pandemic isn’t just economic:”

-

- “Over three in four individuals and organizations reported very high or high levels of anxiety (76% and 79% respectively).

- “This is three times greater than self-reported levels of anxiety before COVID-19 (26% and 25% respectively).

- “Over three times as many individuals AND organizations report very high or high levels of stress and anxiety today (79%) as compared to before COVID-19 (25%).” [emphasis added].

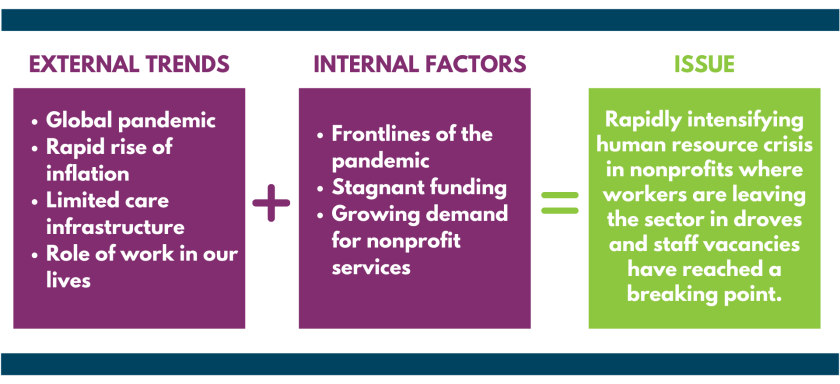

In the general field of nonprofit organisations, the Ontario Nonprofit Network (2021) reports:

A rapidly intensifying human resource crisis in nonprofits, compounded by the pandemic, is threatening the sector’s impact. Over the past few months ONN has been hearing from its network that workers are leaving the sector in droves and staff vacancies have reached a breaking point. It appears that our sector may be facing at least one of the following phenomena across its industries: the great resignation (there are enough people to work but they do not want to work in the jobs available) and/or a labour shortage (there are not enough people to work in the available jobs).

Absent specific museum-related data from the survey of museum working conditions recommended by Thistle (2019a), in recent posts your blogger has adduced evidence that similar outcomes are in fact occurring among museum workers too.

Beyond the above arts-focussed research, an April 2021 survey by the American Alliance of Museums (2021) titled “Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 on People in the Museum Field,”

. . . reported a grave toll on their mental health and wellbeing from the pandemic, rating this impact at an average of 6.6 out of 10 (where 10 indicates very strong negative impact). Nearly half of paid museum staff [demonstrably already working as ‘fully loaded camels’!] reported increased workload. . .

The younger cohort among respondents to the AAM survey averaged 7.8 & students 8 in the above workload question. In the full report, burnout also was reported by 57% of paid staff members as one of the biggest barriers to their staying in the field [emphasis added] (American Alliance of Museums 2021: 6, 5, 8). Oleniacz (2021) finds the identical tendency among educators in museums & zoos.

In the related AAM Center for the Future of Museums (CFM) blog post “Combatting Burnout in the Museum Sector,” CFM’s founder & Director, Elizabeth Merritt (2021) states:

A particularly troubling finding from the survey: one-fifth of museum staff think it is unlikely they will be working in the museum sector in three years and cite burnout [as] a significant barrier to remaining in the field.

Other recent investigations of museum working conditions also identify burnout concerns, including a report that GLAM organisations are negatively impacting their workers by “setting overly ambitious agendas that they do not have the agency or ability to deliver successfully” (Stimler 2020: 4-5). In practical terms, the stresses arising from such unrealistic expectations are “not only unsustainable but also actively harming the field as a whole” (Collections on Contract 2020) [emphasis added].

In the American Alliance of Museums’ Center for the Future of Museums TrendsWatch 2019 Merritt (2019: 44, cf. 43, 47) reported, “nonprofit workers often feel overworked and that their productivity drops when the workweek reaches 50 hours or more. . . 30 percent of the nonprofit workforce was experiencing burnout, and another 20 percent was at risk.”

Highly respected Associate Professor Emerita of Museum Studies at George Washington University, Martha Morris (2019), also has identified that there are “declining levels of employee satisfaction and retention, stemming from stresses like long hours and low pay, . . . unfair treatment and dismay.” In her powerful & rather influential article, former emerging museum professional Claire Milldrum (2017) revealed 4 years ago that she had “left the field because I decided I was very tired . . . [and had] reached my (un)reasonably high tolerance for giving away my labor through volunteering and internships”.

In so many words therefore, “all” the above describe burnout among museum workers just as I have been arguing here on the Solving Task Saturation blog since 2012 & otherwise for more than 3 decades now (Thistle 1990).

In the wider world of work outside the museum industry, a major Canadian health care provider states the following in reference to burnout at work, “We have to get at this now, or else mental health claims at staggering levels are going to be the new norm” (Sanofi Canada 2020: 8, cf. 9, 35) [emphasis added].

In the USA, the Highly Engaged but Burned Out report also finds, “Nearly half of all employees were moderately to highly engaged in their work but also exhausted and ready to leave their organizations” (Moeller et al. 2021: 32) [emphasis added]. Your blogger believes strongly that this crucial risk management advice above must be accepted & acted upon by employers & professional museum organisations in the museum industry as a VERY HIGH PRIORITY.

Additionally, while in the midst of drafting this post, I was informed by one of the authors (Lorraine Bell) about a critically significant report released on 22 September 2021. In-depth interviews with 20 paid museum executive directors concerning their relationships with governing boards was sponsored by the British Columbia Museums Association (BCMA) & the Vancouver Foundation. It identifies some extremely disturbing problems. These include, “governance challenges contributed to workplace stress, ‘burnout’; job precarity and job leaving” (Willard & Bell 2021: 4). Among the troubling findings from various interviewees are:

. . . feelings of isolation. . . found limited or no recourse for their concerns. Many reported workplace stress and feeling ‘burned out’, and in some cases reported taking stress-leaves and/or leaving their positions or the sector . . . “I have to leave the museum. I have worked so hard to build my career in the museum industry…it’s over, I can’t do this anymore.”. . “had no time for family life and personal life” and that there was “zero work-life balance”. . . I couldn’t see myself staying. . .It just felt like it was so broken. I was a hundred percent burned out. . . So I actually went on a three-month stress leave first. . . After [it], I just really felt I couldn’t even bear to go back. And just thinking about going back actually made me feel physically sick” (Willard & Bell 2021: 3, 21, 22) [emphasis added].

As Robert Janes (2009: 64) had observed 12 years ago, many museum directors continue to be “hopelessly overburdened.” Is this not a terribly sick state of affairs in the museum industry? As your blogger has been arguing for many years now, it is important to point out that interview report authors Michelle Willard & Lorraine Bell (2021: 22) conclude, “The overall similarity of experiences amongst a wide variety of organizations indicates that this problem is systemic rather than isolated” (Willard & Bell 2021: 22) [emphasis added]. Please stay tuned to this blog for a full review & analysis of this critically important research project.

In conclusion therefore—seemingly thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic—like the BCMA & AAM, it has become blatantly obvious that other professional museum organisations MUST finally acknowledge in late 2021 that burnout is indeed a serious problem among paid and volunteer staff in the museum field that requires immediate risk management action by all stakeholders!

This understanding reinforces the evidence that had been accumulating in published reports since the 1980s (Thistle 2019)—during the course of which many stakeholders either denied its existence or asserted nothing could be done about it. For references to the evidence of such unheeding responses from managers in the museum field, see the “Responses to the Task Saturation Dilemma” section in Thistle (2017: 4-8 passim). Also search this blog for “burnout” linked in the References Cited entry Thistle (2012-2021) & attend to those posts in 2021 for access to the recent mounting evidence.

Solutions:

Among the coping mechanisms provided by professional museum organisations are, for example, the Ontario Museum Association (2021) recommends get outside, write it out, take deep breaths, step back from the stressful situation. As I have argued elsewhere (Thistle 2021) however, such an emphasis on ‘self-care’ fails to comprehend that ignoring “root causes” of the rampant enervation of museum workers will NEVER begin to deal effectively with the prime sources of the problem of museum worker burnout. Sociology of work scholars have determined that employers’ exploitation of workers to the point of abuse are the primary causes of overload that leads to burnout (cf. Posen 2013: 5, 38, 45, 321; Duxbury & Higgins 2012: 4-6; Green 2006: 57).

Certainly, the Ontario Museum Association is to be highly commended for the following statement:

. . . while practicing and promoting self-care is beneficial, too often the onus ultimately falls to the individual. The employer’s role is to be conscious and supportive of their employees’ potential need for self-care. More importantly employers need to better recognize the potential underlying issues within their workplace culture that contributes to employee need to engage in self-care practices. Moreover, employers need to be responsive in a way that better addresses the issues at hand [emphasis added].

During COVID-19 lock downs, my following cry is not often heard these days but, to the Ontario Museum Association, I say “BINGO!”

Although immediately qualified, even the Harvard Business Review (HBR) concurs:

Research has definitively shown that burnout is an organizational problem, not an individual one [emphasis added] (Yu & Schabram 2021).

Flowing from the OMA & HBR statements of fact above, your blogger recommends in the strongest possible terms that “all” museum industry stakeholders—including board members—also attend with utmost diligence to the Center for the Future of Museums 14 December 2021 post “Forecasting 2022:”

Consider: how might your organization support staff, and reduce turnover, in a third year of pandemic stress? Are you monitoring the long-term impact of the crisis on staff at all levels, and how can you mitigate that impact through your policies, procedures, wages, and benefits? (Merritt 2021b) [emphasis added].

I caution my readers here that most COVID-19 solutions offered to museum workers to date—including Merritt (2019)—seem solely focussed on training to ‘make museum workers stronger’ [to enable them to shoulder ever more new burdens] and/or self-care (Thistle 2021). Of course, I maintain that stakeholders in the museum industry can have only one priority at this stage: ‘getting at burnout risk management NOW’ (cf. Sanofi Canada 2020: 8).

I reiterate again, “all” stakeholders in the museum industry must focus on actually improving the fundamental quality of working lives in museums to protect museum worker mental, physical, family, & social health—to say nothing about their productivity! Please refer to my 24 May 2021 blog post here Solving Museum Worker Burnout & the ‘Immorality of Inaction’: FIX CAUSES (vs. Solely Symptom ‘Self-Care’) (Thistle 2021).

References Cited: [please report any dead links using the Contact function above]

American Alliance of Museums. 2021a. “AAM Announces Findings from Impact of COVID-19 on People in the Museum Field Survey.” Press Release, Posted on Apr 13, 2021 t https://www.aam-us.org/2021/04/13/aam-announces-findings-from-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-in-the-museum-field-survey/ link to full report at https://www.aam-us.org/2021/04/13/measuring-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-in-the-museum-field/ (accessed 2 December 2021).

American Alliance of Museums. 2021b. COVID-19 Resources & Information for the Museum Field” at https://www.aam-us.org/programs/about-museums/covid-19-resources-information-for-the-museum-field/ (accessed 10 December 2021).

Borodenko, Nicholas. 2021. National Arts and Culture Impact Survey: Organizations Report. Ottawa: Prairie Research Associates released in January 2021 at http://bit.ly/nacis-individual-report cf. Ontario Individuals at http://bit.ly/nacis-ontario-individual-report (accessed 10 December 2021).

Collections on Contract. 2020. “Unsupported, Uninsured, Unsustainable: The effect of contracting on young professionals.” posted February 20, 2020, updated December 11, 2020 9:58 p.m. at https://collectionsoncontract.com/2020/02/20/unsupported-uninsured-unsustainable-the-effect-of-contracting-on-young-professionals/ (accessed 14 December 2021).

Duxbury, Linda and Higgins, Christopher. 2012. Revisiting Work-Life Issues in Canada: The 2012 National Study on Balancing Work and Caregiving in Canada. Ottawa: Carleton University and the University of Western Ontario http://newsroom.carleton.ca/wp-content/files/2012-National-Work-Long-Summary.pdf (accessed 23 March 2021).

Green, Francis. 2006. Demanding Work: The Paradox of Job Quality in the Affluent Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Janes, Robert R. 2009. Museums in a Troubled World: Renewal, Irrelevance, or Collapse? New York: Routledge.

Merritt, Elizabeth. 2021a. “Combatting Burnout in the Museum Sector.” Center for the Future of Museums Blog posted on May 5, 2021 at https://www.aam-us.org/2021/05/05/combating-burnout-in-the-museum-sector/?utm_source=American+Alliance+of+Museums&utm_campaign=ac77c27952-Dispatches_May6_2021&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f06e575db6-ac77c27952-37245349 (accessed 14 December 2021).

Merritt, Elizabeth. 2021b. ”Forecasting 2022, Part 1: Waves Ahead” Center for the Future of Museums Blog Posted Dec 14, 2021 at https://www.aam-us.org/2021/12/14/forecasting-2022-part-1-waves-ahead/?utm_source=American+Alliance+of+Museums&utm_campaign=3ad303720d-Dispatches_DecD16_2021&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f06e575db6-3ad303720d-37245349 (accessed 17 December 2021).

Merritt, E. 2019. TrendsWatch 2019. Washington: Center for the Future of Museums, American Alliance of Museums. [free summary available https://www.aam-us.org/programs/center-for-the-future-of-museums/trendswatch-2019/ (accessed 14 December 2021).

Milldrum, Claire. 2017. “Why I Left The Museum Field: A Guest Post By Claire Milldrum.” ExhibiTricks: A Museum/Exhibit/Design Blog 11 September http://blog.orselli.net/2017/09/why-i-left-museum-field-guest-post-by.html (accessed 14 December 2021).

Moeller, Julia et al. 2021. Highly Engaged but Burned Out: Intra-Individual Profiles in the US Workforce. Charlottesville, VA: OSFPREPRINTS Center for Open Science Peer-reviewed Publication DOI 10.1108/CDI-12-2016-0215 at https://osf.io/h6qnf/download (accessed 11 December 2021.

Morris, Martha. 2019. “Reinventing Museum Careers.” American Alliance of Museums Career Management web page blog posted on November 18, 2019 https://www.aam-us.org/2019/11/18/reinventing-museum-careers/ (accessed 14 December 2021).

Oleniacz, Laura. 2021. “More Than Half of Museum, Zoo Educators Weighing Career Change, Survey Finds.” North Carolina State University News posted December 6, 2021 at https://news.ncsu.edu/2021/12/more-than-half-of-museum-zoo-educators-weighing-career-change-survey-finds/?utm_source=American+Alliance+of+Museums&utm_campaign=4c9b89c16f-Dispatches_Dec09_2021&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f06e575db6-4c9b89c16f-37245349 (accessed 9 December 2021).

Ontario Museum Association. 2021. “COVID-19 Resources” web page at https://members.museumsontario.ca/resources/tools-for-museum-practice/COVID19 Updated: October 20, 2021 [also see search for OMA COVID-19 resources at https://members.museumsontario.ca/search/node/COVID-19 ] (accessed 10 December 2021).

Ontario Nonprofit Network. 2021. “The Nonprofit HR Crisis.” at https://theonn.ca/our-work/our-people/nonprofit-hr-crisis/?mc_cid=1fe18f7fe7&mc_eid=6e9d5c1350 (accessed 17 December 2021).

Posen, David. 2013. Is Work Killing You? A Doctor’s Prescription for Treating Workplace Stress. Toronto: House of Anansi Press Inc.

Sanofi Canada. 2020. The Sanofi Canada Healthcare Survey 2020. Sanofi Canada, Laval, PQ https://www.sanofi.ca/-/media/Project/One-Sanofi-Web/Websites/North-America/Sanofi-CA/Home/en/Products-and-Resources/sanofi-canada-health-survey/sanofi-canada-healthcare-survey-2020-EN.pdf?la=en&hash=F1C763AA6B2F32C0BF2E623851FD05FD (accessed 20 December 2021).

Stimler, Neal. 2020. WHITE PAPER: GLAMs’ (GALLERIES, LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES, AND MUSEUMS) DYNAMIC SUSTAINABILITY PLATFORM STRATEGY. SAN DIEGO, CA: Balboa Park Online Collaborative (BPOC), BPOC.ORG posted October 6, 2020 at DOI: https://doi.org/10.47786/TLOU3193 (accessed 14 December 2021).

Thistle, Paul C. 2021. “Solving Museum Worker Burnout & the ‘Immorality of Inaction’: FIX CAUSES (vs. Solely Symptom ‘Self-Care’).” Solving Task Saturation for Museum Workers blog posted 24 May 2021 at https://solvetasksaturation.wordpress.com/2021/05/24/solving-museum-worker-burnout-the-immorality-of-inaction-fix-causes-vs-solely-symptom-self-care/ (accessed 20 December 2021).

Thistle, Paul C. 2019a. “QWL Resolution for 2019 CMA Toronto AGM.” Solving Task Saturation for Museum Workers blog posted February 27, 2019 at https://solvetasksaturation.wordpress.com/2019/02/27/qwl-resolution-for-2019-cma-toronto-agm/ (accessed 20 December 2021).

Thistle, Paul C. 2019b. “Does public history work itself require repair?” History@Work blog posted 20 February. Indianapolis, IN: National Council on Public History https://ncph.org/history-at-work/does-public-history-work-itself-require-repair/#_ednref4 (accessed 10 December 2021).

Thistle, Paul C. 2017. “Fully Loaded Camels: Addressing Museum Worker Task Saturation.” Solving Task Saturation for Museum Workers blog located at https://solvetasksaturation.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/fully-loaded-camels-2017.pdf (accessed 21 August 2017).

Thistle, Paul C. 2012-2021. Solving Task Saturation for Museum Workers blog search for “burnout” at https://solvetasksaturation.wordpress.com/?s=burnout (accessed 15 December 2021).

Thistle, Paul C. 1990. “Editor’s View.” Museum Scene No. 38, August 1990, p. 1 (The Pas, MB: Sam Waller Little Northern Museum) at https://solvetasksaturation.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/littlenorthernmuseumeditorial.pdf (accessed 6 April 2021).

Willard, Michelle & Bell, Lorraine. 2021. Governance Challenges and Opportunities in B.C.’s Small to Medium Non-profit Museums : A conversation with past and present Executive Directors about what needs to change and how to change it. Vancouver: British Columbia Museums Association, mighty Museum, & Vancouver Foundation posted September 22, 2021 at https://museum.bc.ca/brain/report-on-small-to-medium-non-profit-museums-governance/ (accessed 7 January 2021).

Yu, Tse-Heng & Schabram, Kira. 2021. “Your Burnout Is Unique. Your Recovery Will Be, Too.” Harvard Business Review posted April 12, 2021 at https://hbr.org/2021/04/your-burnout-is-unique-your-recovery-will-be-too (accessed 20 December 2021).